Last year, I worked as an interpreter for a young student with CHARGE Syndrome. While the student was in a program for children with special needs, she was the only student in the school with CHARGE. CHARGE can cause deafness and blindness, as well as physical and cognitive complications. In Alex’s case (whose name has been changed), she has cognitive delays (congruent with learners who are deaf-blind), has blurred vision in part of her visual field, balance issues, low musculature, pain from constipation, some repetitive behavioral tendencies, and self-stimulating physicality—similar to those observed in children with autism. These behaviors may include clapping, tooth grinding, and tense jumping. This job was not what interpreters are trained as in terms of “typical interpreting.” As such, the work constantly generated questions and challenges for me about my role and daily practice. Like many educational interpreting jobs, issues arose about the meaning of true inclusion, as these issues were all the more heightened by physical disability and neurodiversity.

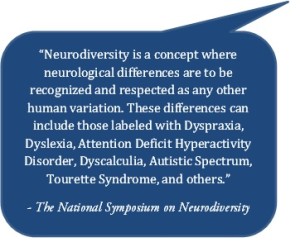

Neurodiversity is a relatively new term, which serves as a paradigm shift away from viewing autism and other neurological conditions as diseases and disorders. Neurodiversity, like biodiversity, views these conditions as a natural manifestation of variety in the human genome. Both of these schools of thought bring something to the table, but in an everyday context—especially in a school—I find the concept of neurodiversity to most beneficial. Neurodiversity brings humanism to the forefront.

For instance, if I had walked into the classroom each day thinking about the negative aspects that CHARGE Syndrome can induce – thinking something like, “I hope Alex doesn’t do xyz bad thing today” – I would already be shaping my view of her and my interactions with her to be negative. With this in mind, I walked into the classroom each morning looking forward to what Alex might accomplish that day with very solid language access support. Beyond this positive outlook, however, there are many tactics and approaches that need to happen in order for neurodiverse Deaf and DeafBlind children to succeed.

I have come to believe that it is ethically acceptable and perhaps necessary for the interpreter of a student with neurodiversity to advocate on behalf of her needs, which are different than the needs of a child who is neurotypical. For instance, if Alex was engaging in a self-soothing behavior, such as grinding her teeth, I would not attempt to stop this behavior, instead, I would acknowledge it aloud to the teacher, saying something like, “it sounds like Alex is grinding her teeth.” If the teachers were busy or no one provided Alex with her tooth chewy (an oral motor device designed to satisfy physiologic stimulatory need), then I would get it for her.

Alex would need periodic sensory breaks, as she can get physically and psychologically overwhelmed. She would sometimes close her eyes in the middle of an activity or instruction. Because of this, I often needed to remind the assistants and teachers when Alex had not seen my interpretation. When she would reopen her eyes, she would usually be attentive, with her eye gaze on me. Being aware of the overwhelming physical demands on an individual who is neurodiverse and prepared with strategies to support such a student significantly impacted the flow of our communication interactions.

Sometimes the teacher would say something like, “come on, Alex,” or “open your eyes,” believing that Alex’s behavior meant that she was avoiding work or being lazy. A few times, one assistant teacher thought that Alex was rolling her eyes in a show of insolence or bad attitude – like a sassy teenager. I was pretty shocked the first time I heard this; of course Alex wasn’t rolling her eyes in that sense! I knew that Alex in all likelihood did not even know that rolling one’s eyes has this linguistic significance.

Sometimes the teacher would say something like, “come on, Alex,” or “open your eyes,” believing that Alex’s behavior meant that she was avoiding work or being lazy. A few times, one assistant teacher thought that Alex was rolling her eyes in a show of insolence or bad attitude – like a sassy teenager. I was pretty shocked the first time I heard this; of course Alex wasn’t rolling her eyes in that sense! I knew that Alex in all likelihood did not even know that rolling one’s eyes has this linguistic significance.

In cases like these, I would say a brief informative phrase such as, “it looks like Alex is just resting her eyes for a moment.” In the case of the latter, I added that children with CHARGE Syndrome experience eye fatigue rather easily which is very different from expressing attitude. This would contextualize Alex’s behavior as a reaction to physical discomfort. This could be a somewhat tricky balance for me — trying to inform the teacher of a “CHARGE moment” without making her feel threatened or like I was crossing the boundary of my role.

Pace was always an issue. I was constantly saying, “just a moment,” or “let me just make sure Alex gets this” as I would wait for Alex’s gaze and attention. Thanks to some of these explanations, the teacher became more attuned to these “CHARGE moments” and our work as an educational team found a better balance.

As the year progressed, and with guidance from the New York Deaf-Blind Collaborative (a federal grant that provides technical assistance and support throughout New York State on behalf of children and young adults with combined hearing and vision loss www.nydbc.org), I found that there were many wonderful tools at my disposal to help with my work – from tactile signing to leg taps to shoulder squeezes to breathing exercises. Ultimately, perhaps the most helpful tool was the one I tapped into before even walking into the room: an acceptance and appreciation for neurodiversity. This attitude allowed me to be positive and comfortable with any day that was expected to go into unexpected directions. I walked in everyday excited to see a child who has different learning abilities and a personality, a student who has language and desires access, a student who deserves patience and modification, a human being who has value.

Look for future articles on this and other topics from Katie Peacock Helde.

RESOURCES

CHARGE Syndrome Foundation - http://www.chargesyndrome.org/

New York Deaf-Blind Collaborative - http://nydbc.org/

National Center on Deaf-Blindness - https://nationaldb.org/

Perkins E-Learning - http://www.perkinselearning.org/videos/webcast/charge-syndrome-overview

American Institute for Learning and Human Development – http://www.institute4learning.com/neurodiversity.php

Classroom Interpreting -http://www.classroominterpreting.org/Interpreters/proguidelines/developmental.asp

Palm Reversal Errors in Native-Signing Children with Autism -http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3479340/