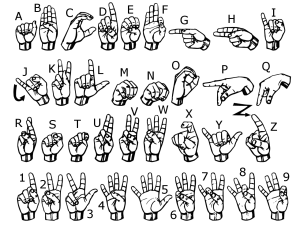

Before Sign Language interpreters were considered professionals worthy of pay, before the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf was founded or a code of ethics was written, interpreters came from the community—hearing people raised in signing families, teachers of the Deaf and signing clergy members—and their service was volunteered. They did not expect to be paid for their work, and no institution or individual making use of the interpreter, such as a doctor, a church, a government agency, expected to foot the bill for the service. Inherent in that practice was the audist notion that Deaf people can make do with an untrained interpreter, whose personal feelings may intrude on the interpretation or whose knowledge of the content may be limited.

Before Sign Language interpreters were considered professionals worthy of pay, before the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf was founded or a code of ethics was written, interpreters came from the community—hearing people raised in signing families, teachers of the Deaf and signing clergy members—and their service was volunteered. They did not expect to be paid for their work, and no institution or individual making use of the interpreter, such as a doctor, a church, a government agency, expected to foot the bill for the service. Inherent in that practice was the audist notion that Deaf people can make do with an untrained interpreter, whose personal feelings may intrude on the interpretation or whose knowledge of the content may be limited.

It is not surprising then, that when RID wrote its first code of ethics, it stated outright that interpreters should not charge for their work, unless they interpreted in court. Why courtroom interpreting alone was carved out as worthy of pay is unclear, but it was not until years later, when the RID Code of Ethics was revised, that it clearly stated that interpreters should be paid for their work as a matter of ethics. Recently, RID began to consider the value of mandating pro bono work on the part of its members. An ad hoc committee is currently exploring the feasibility of requiring a minimum amount of free interpreting service professional interpreters must provide to maintain their certification or membership. While this may not be the profession coming full circle back to a mandate for free service provision, it is perhaps a spiral: revisiting the idea of providing free service, while still moving the profession forward.

While RID’s working group considers what service to require of RID members, Sign Language interpreters must make their own professional and personal decisions as to where to donate their time. When I am asked to donate my interpreting services, I consider whether my donation is aiding the Deaf community by providing access, or saving a company money, which is otherwise legally bound to provide interpreters. Case in point: a Fortune 500 corporation holds a large event every year to raise money for cancer research. I support the cause, naturally, and I believe that the event should be accessible to the Deaf community. However, the corporation, a multi-million dollar operation, is paying for the stage, audio equipment, caterers, and the production of commemorative t-shirts. Paying for some services but not interpreters strikes me as regression to the old audist assumption that interpreters should work for free, that Deaf people can make do with whoever is willing to volunteer, and money is best spent on other expenses. To interpret that event for free seems to me doing a service for the company more than for the Deaf attendees.

Now consider a Deaf person wants to meet with a lawyer who has been recommended to her. She contacts the lawyer to ask for a meeting and asks that he provide an interpreter. The lawyer is a solo practitioner and is not required under the Americans with Disabilities Act to provide an interpreter. This is a situation where I would be happy to offer my services, as it is the Deaf person who would benefit from a skilled interpreter, to which, unfortunately, the law does not state she is entitled. The lawyer is not shirking his duty to provide access under some bigoted concept of what Deaf people deserve. He simply cannot absorb the cost. Here, everyone wants the meeting to proceed smoothly, and there is respect for the Deaf client’s rights. It’s simply an issue of money. And that’s where an unpaid interpreter can truly make a difference.

When considering pro bono work, I encourage interpreters to expand their definition to include the multiplicity of ways we can support our Deaf consumers.

- Consider working when you normally do not—evenings, weekends, religious holidays—and donating the money you earn to an organization that aids the Deaf community or works to provide access.

- When a job runs past its end time, and you are aware you will not be paid past that time, stick around and let your consumers finish their meeting. It means working for free, and you have the contractual right to leave, but staying allows the consumers to complete their meeting, and not be at the mercy of a scheduler who set the interpreter’s stop time.

- Contribute skills other than interpreting to a Deaf organization by building a website or drafting contribution solicitation letters for a Deaf-owned or Deaf-led business or social group.

- Provide interpretation while Deaf community members donate their time at a non-profit or charitable organization. Perhaps a group of Deaf volunteers would be eager to work at a soup kitchen, or clean a park, or work for a political candidate, if interpreters were available.

- Volunteer to help set up for a Deaf event, to clean up after, or to otherwise help a community event run smoothly.

- Support Deaf artists by working on their sets or in their studios, buy tickets to see their work and buy their art.

Many interpreters, including me, owe our careers to the Deaf friends and teachers who taught us ASL and opened the door to the Deaf community that we may enter. Donating some time, effort and funds is the least we can do to give something back.