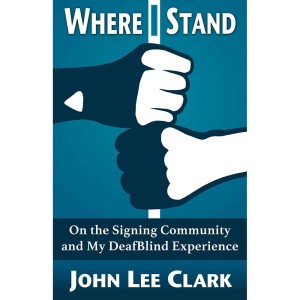

“IN THAT SPACE, WE ARE THERE”: John Lee Clark’s Where I Stand: On the Signing Community and My DeafBlind Experience. A reflection by T. K. Dalton

John Lee Clark opens his brilliant essay collection Where I Stand with a burst of poetry: “As a DeafBlind person, standing for me is almost never about being still or in one place.” He describes waiting for a bus, marking time with his feet in order to observe his surroundings. Communication intensifies this habit, he writes, especially when that dialogue is between DeafBlind people: “I would always find myself emerging from an engrossing conversation standing in a different place.” Interpreters who read Clark’s collection may finish the book with a similar reaction. On any given workday, a freelancer can encounter a hearing consumer with no knowledge of ASL, followed by another who views deafness as a medical malady, then by and a third with deep knowledge of the culture, all before lunchtime. Clark’s essays show an equally impressive span, offering insight in equal measure to community insiders, newcomers and novices, and complete outsiders. As skilled an essayist as he is a poet, he deftly adjusts each argument–”Does Disability Really Need to be Fixed?”, “A Cochlear Implant Thought Experiment,” “Why Hearing Parents Don’t Sign”–to match its audience and, importantly, to challenge the assumptions that audience might hold. His work isn’t “for hearing people only,” either. Clark writes one of the clearest explorations of why people “quit” the Deaf community I have ever encountered in “Great Expectations,” an essay that grows to pose a universal question of what any community can and cannot do for its members.

Like any great collection of ideas, these live beyond the printed page. One essay, “An Open Letter to American Heritage Dictionary”, led to an actual revision of the newly-added term “audism.” Another excellent piece, “ASL and the Star-Spangled Banner”, has also resonated with Deaf audiences. The remarkable re-thinking of the national anthem as a more accurate and contextualized visual narrative led to this amazing re-rendition by the Rocky Mountain Deaf School. The translator team of fourth and fifth graders also produced an impressive self-analysis. Here, and throughout Where I Stand, Clark brings attention to language as both a means to social justice for his community and as an aesthetic end worthy on its own. He is, after all, a poet. The insights into community life should make the collection required reading for anyone involved in the Deaf-World. But interpreters, after all, are language people, and Clark’s thoughts on poetry in English and in ASL will invigorate anyone who cares about language. He devotes a whole essay to Paul Hostovsky, a talented poet who works as an interpreter. In an essay that appeared in the prestigious magazine POETRY, Clark reviews two centuries of poetry by American Deaf people. (He edited the groundbreaking anthology Deaf American Poetry as well as, in the interest of disclosure, the anthology Deaf Lit Extravaganza, to which I contributed fiction.) Clark compares the brilliance of performed ASL poetry to the dearth of recorded ASL literature, and pithily diagnoses the latter with a “movie problem.” The lack of ASL literature, he argues, stems from the medium itself, and the ingrown problem that performed video differs fundamentally from written text. A written text, he writes, “creates space for us to say things as ourselves. And it creates space, when we are reading it, to fall into that text. In that space, we are there. And that’s how ASL literature will finally get there, too.” Theorizing about the medium of a message could quickly become overly abstract. To Clark, though, medium is a message. One crucial meta-message reflects his experience of (in)accessible media. On one extreme, he writes comically about his thwarted attempts to abandon heavy Braille issues of magazines in “All the Things I Can’t Leave Behind.” Conversely, the lack of these heavy tomes leads him to pose “A Question That’s Harder Than It Should Be”: Should Clark-the-poet send his work to magazines that Clark-the-reader cannot, well, read? The aforementioned POETRY magazine, Clark says, is the only poetry journal to offer hard-copy issues in Braille. (Anyone, then, can read his poem “My Understanding One Day of Fox Gloves.”) Where I Stand closes with essays on the author’s particular DeafBlind experiences, and these are the most moving, the most personal. While Pro-Tactile and Skyways and changing attitudes make this “an exciting time to be DeafBlind”, our age is not perfect. “I Didn’t Marry Annie Sullivan” debunks the assumptions Clark confronts regarding his personal life, and “Unreasonable Effort” rails against the institutional challenges faced by DeafBlind college students. Throughout the collection, Clark slaloms gracefully through his arguments’ logic. He extols writers with disabilities to write about people with disabilities. He parodies ‘people first’ language where a DeafBlind character struggled to run an errand at a social service agency where the new red tape is the zealous application by staff of politically correct terminology. Clark describes his school for the Deaf in exquisite detail in a piece that first appeared in Deaf Lit Extravaganza. This piece shows the subtlety that is Clark the essayist at his best. Clark’s vision has changed over time, and those changes permeate the piece powerfully. Deaf schools, of course, have unrivaled importance in the formative experiences of many Deaf people. For Clark, the beauty of the Minnesota State Academy for the Deaf “encouraged [him] to use a cane and retire [his] eyes to a life of leisure.” This particular place, remembered by this particular author, exists in memory only. This is true for any alumna, but the nostalgia takes on a potent edge, because this is a place the remember-er can no longer see. But the embedded power is this: the speaker forgoes eyesight, overrules its necessity, using language and memory to share with everyone his vision. To learn more about John Lee Clark go to: www.johnleeclark.com For more information on the blogger visit: www.tkdalton.com/