Just in time for Tony Sunday: the tale of an actress who never expected to see her name in lights. Jamie Wax has her story…

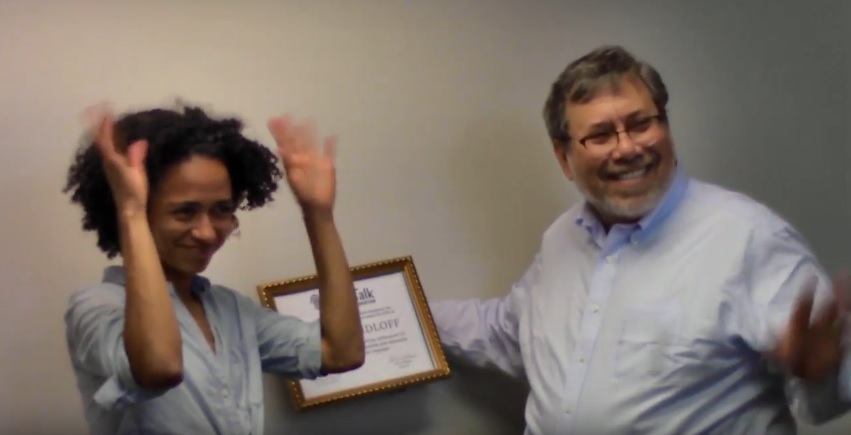

What’s the best story on Broadway? Consider this: At age 40, Lauren Ridloff, a stay-at-home mom with no professional theater experience ever, and who is deaf, was offered a starring role.

“Is there a part of you that still can’t quite believe it’s real?” asked Wax.

Joshua Jackson and Lauren Ridloff in “Children of a Lesser God.” Photo by Matthew Murphy

“A part of me? No, all of me!” she laughed.

And Ridloff put all of herself into the performance in the revival of “Children of a Lesser God.” She plays Sarah, a cleaning woman at a school for the deaf who falls in love with an able-hearing teacher, played by Joshua Jackson.

When asked how unusual Ridloff’s story is in the business. Jackson said, “Oh, she’s a one of one. She is a totally unique woman, person, mother, and now actor.”

Ridloff was born deaf to hearing parents. As a child, she worked on using her voice to speak, but spending time at a camp with kids and counselors who communicated only with sign language, led to an awakening, as Lauren told Wax through her interpreter, Candace Broker Penn:

“And for the first time, I never had to use my voice to communicate clearly with anyone. And I realized I could speak without thinking so much about how to say what I had to say.

“So, when I got back home, I really told my family, in a sense I ‘came out’ to my family. I said, ‘I’m not going to use my voice anymore.’ And my family accepted that, and accepted who I was.”

She was asked, “Does this feel like a dream? “It’s a wonderful dream!” she replied.

To see the interview with Lauren, please see CBS News’ full article at https://www.cbsnews.com/news/tony-nominee-lauren-ridloff-children-of-a-lesser-god/

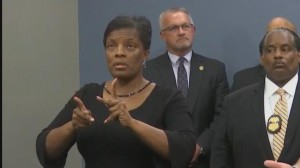

I recently found myself pulled into an argument on Facebook, responding to a friend’s post about Derlyn Roberts, the woman appearing to interpret a news conference by law enforcement in Florida.

I recently found myself pulled into an argument on Facebook, responding to a friend’s post about Derlyn Roberts, the woman appearing to interpret a news conference by law enforcement in Florida. To my interns current and former:

To my interns current and former:

Last month, a local Fox News station

Last month, a local Fox News station  From time to time interpreters confide in each other about a job that has gone terribly wrong. From time to time, we find ourselves completely overwhelmed, unable to keep up with the speaker, and at a loss for words or signs. If it happens too often, we question whether we should be interpreters at all. We console ourselves and each other by saying that if we never find ourselves challenged by a job, then we’re probably not stretching ourselves enough, not enhancing our skills or our capacity to master more complicated and difficult interpreting experiences. And while it’s necessary for interpreters to take risks and do the jobs that scare us a little, it is sometimes accomplished at the expense of our consumers. For although we should make every effort to grow and hone our skills, we never want to block their access in order to give ourselves a chance to do something challenging and new.

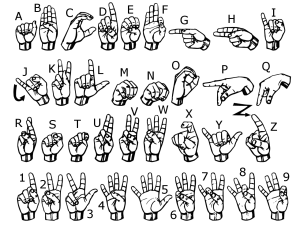

From time to time interpreters confide in each other about a job that has gone terribly wrong. From time to time, we find ourselves completely overwhelmed, unable to keep up with the speaker, and at a loss for words or signs. If it happens too often, we question whether we should be interpreters at all. We console ourselves and each other by saying that if we never find ourselves challenged by a job, then we’re probably not stretching ourselves enough, not enhancing our skills or our capacity to master more complicated and difficult interpreting experiences. And while it’s necessary for interpreters to take risks and do the jobs that scare us a little, it is sometimes accomplished at the expense of our consumers. For although we should make every effort to grow and hone our skills, we never want to block their access in order to give ourselves a chance to do something challenging and new.  Before Sign Language interpreters were considered professionals worthy of pay, before the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf was founded or a code of ethics was written, interpreters came from the community—hearing people raised in signing families, teachers of the Deaf and signing clergy members—and their service was volunteered. They did not expect to be paid for their work, and no institution or individual making use of the interpreter, such as a doctor, a church, a government agency, expected to foot the bill for the service. Inherent in that practice was the audist notion that Deaf people can make do with an untrained interpreter, whose personal feelings may intrude on the interpretation or whose knowledge of the content may be limited.

Before Sign Language interpreters were considered professionals worthy of pay, before the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf was founded or a code of ethics was written, interpreters came from the community—hearing people raised in signing families, teachers of the Deaf and signing clergy members—and their service was volunteered. They did not expect to be paid for their work, and no institution or individual making use of the interpreter, such as a doctor, a church, a government agency, expected to foot the bill for the service. Inherent in that practice was the audist notion that Deaf people can make do with an untrained interpreter, whose personal feelings may intrude on the interpretation or whose knowledge of the content may be limited.